The Romance of Brick

by G. Burton Long, 1971

Brick is something that has been with us for centuries. There is an old maxim which says, “Familiarity breeds contempt,” and this might well be applied to brick, because it has been used as a building material throughout the ages, and we are prone to accept it without regard to its antiquity or to its continued use or to the function it has played in the development of civilizations from the very first of recorded time. Some people claim that the first brick were made some twelve thousand years ago. You would have an awfully hard job to prove that point. Yet if you will ever read your Bible, you will see in it many references to brick, notably the Tower of Babel. There were also a good many ancient temples that were built of brick.

The first recorded example of brickwork comes from the Egyptians. Brickwork has also been found in many excavations in Mesopotamia, especially in Ur. Those brick were large unburned units and later had the impression of the cartouche of the king on them, which reveals their ages. The brick I am holding in my hand is somewhere in the neighborhood of thirty-five hundred years old. That is proved by the inscription on its front. This is not a facsimile; it’s the real thing. In those days they were unburned, because the climate did not require them to be burned. These are really and truly brick made from clay and straw. Here is another one that is maybe a thousand years younger. Again sun-baked, this has been scuffed by the ages. The little hole here is so that you can carry it easily. Some of the other outstanding examples of brickwork from antiquity were made by the Romans. From them comes a brick which bears their name even today. You have all seen it—approximately twelve inches long, an inch and a half thick, and three and a half or four inches deep. They are the ones that conquered England and brought a new type of building, and today you have brick buildings in England which were built by the Romans. I believe that it was they who first glazed brick. You have all seen glazed brick; of course at first it was a very crude process, but you have to give them credit for it. Very peculiarly, no brick were manufactured in Europe from the end of the fourth century to the middle of the thirteenth, and then a new trend set in.

So much for the Old World past. In what is now the United States, the first brick were manufactured about the middle of the seventeenth century, but it was not until the latter half of the nineteenth century that we really manufactured sufficient brick to take care of the needs of the area. This was all done through the invention of machinery by the English. The first brick kiln was probably built in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1629. You’ve all heard the story and it is easily proved that they had small brickyards on what is now the Boston Common. By 1776 there were a good many houses in Boston that are still there today that were in some measure built of brick. Most of these brick were brought over from England as ballast in the ships, and it was not until much later that there was sufficient manufacture here to take care of the local needs. Brick are still used as ballast. Directly after the war we received an order from South America, and that brick went almost free of charge for it was used as ballast for the ship.

The oldest brick house in this vicinity is not in Cambridge, unfortunately, but in Medford—the Tufts house, built around 1676, sometimes called the Cradock house. But here in Cambridge you have at Harvard Massachusetts Hall, built in 1720, gutted three times by fire, and still being used today, which is quite a remarkable feat for a building.

Brick are made from clay or shale, and according to the consistency of the shale or clay the brick comes out yellow or shades thereof or red. It is a natural process, a natural coloring deposited by nature. The first brick as you saw it here were put in some sort of a form; the clay was put in by hand and dumped in some way or other and was dried by the sun. Surprisingly, right up to 1930 the New England Brick Company made brick in that fashion, and just as surprisingly they had to be called Harvard water-struck brick. Water-struck was one type and sand-struck was the other. The water was used in the molds to prevent the brick from adhering to the side of the mold, and if you used sand, you had a sand-struck brick. While we are on that subject, here is a good old Nebco of later days, mass-produced, and that’s sand-struck brick. In the handmade brick, made in a water mold, you can readily see the water creases.

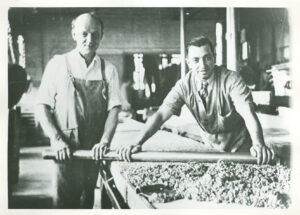

Originally, a sand-struck brick was turned out basically for inexpensive work and for the inside of a building, called backup brick; and the water-struck brick was used for a facing brick. Because of its use around 1890, a particular gate at Harvard College —the Johnston gate—was deemed by architects to be something quite unusual, and that began a series of activities here in this area for water-struck brick that today is still unbelievable. The brick were manufactured almost as they were hundreds of years ago. You had a horse and a plough and you ploughed the clay bed, and then you rolled over it with a harrow. Then you picked the clay up and put it in a “soaking pit” and mixed in a certain amount of sand, and then you poured water on it so that it got into a homogeneous mass. Then a man with a shovel came and stirred it up every now and again. That would sit for a week or ten days. The next step made use of a machine, if you will flatter it with that title, that was like a big ice-cream freezer with a beater inside. Coming from that beater on the end of it was a horse, and he walked around in a circle all day long and the clay was exuded from the front of the machine, scooped up a handful at a time, and put in brick molds which had previously been dipped in water. These molds were trotted out onto a flat bed of clay. They had false bottoms, which were moved to relieve the pressure and prevent the brick from sticking to them. The brick were put there to dry by the sun. Interestingly, if you had too much sun, the top of the brick would dry too quickly; you would then have uneven shrinkage and the brick would split open, so it was shaded with burlap or some similar material. The other misfortune was that in case of rain you had to run out and cover them with burlap again.

When they were dumped, the brick were laid on what was called “the flat.” After they had been there a sufficient length of time to handle they were then what you call “edged,” so that the sides got the wind, the sun, and the air; and when they were further dried, they were put in “hacking sheds.” The brick were stacked far apart so the wind could blow through them. So you see there was not much money spent for fuel for drying. These brick were then put in “stove kilns,” built brick by brick, with tunnels left for putting the fire through. A shell of rejected brick was then put on the outside and daubed over with clay and sand, making an oven. You built it up and then you tore it down—a very wasteful and expensive habit, all changed today of course. But the only reason Harvard water-struck brick aren’t made today the way they were in the 1930s is that you can’t get the help to do it, believe it or not. And today that brick, which at one time sold at a job in Portland, Maine, for $6.00 a thousand, costs around $110-$120 a thousand.

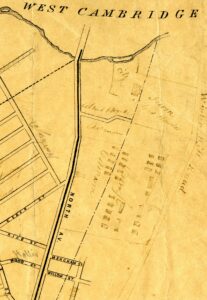

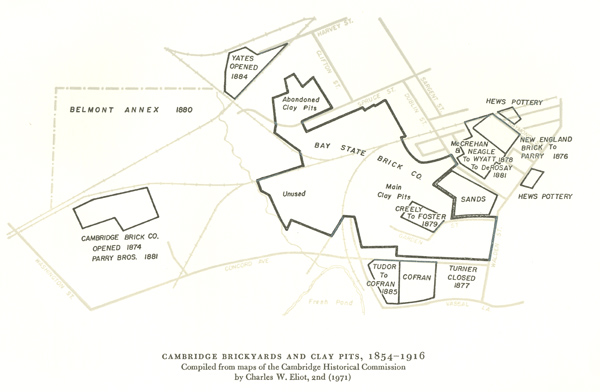

So much for the brick part of it. Let us see if perhaps we can come into something of historical interest to you. All of the various areas that have been laid out on these maps represent places where brick were made. In most instances there were individuals who owned and operated a brickyard. It was an out-and-out family affair, more particularly in New Hampshire, where some farmers built a brick kiln every year. When the planting was all done, they built a brick kiln and they sold it—they burned it in the winter and they sold it next spring. That’s the way they filled their spare time. On the west side of the cemetery near Rindge Avenue, perhaps the most famous of all the holes was Jerry’s Pit, still with us today, still performing some degree of usefulness as an old swimming-hole for kids. No one knows how it got there, but someone left the hole and there you are.

On May 2, 1863, the Bay State Brick Company came into existence. In those days a capitalization of $300,000 was quite a deal, and contrasted strongly with the smaller yards which continued to be individually owned and operated. Among the directors listed in 72 1883 were some people whose family or whose names you may know. There was Samuel A. Carlton, Charles F. Fairbanks, Joshua T. Foster, Gustav Heinecke, John H. Hubbell who was president of the board, John E. Sanford, and Thomas J. Whidden (I wonder if he was any relation to the contractor of the same name).

One of the interesting things to me, which I never realized until Professor Eliot made this map, was that all of the claypits and brickyards in Cambridge seem to be centered in this one locale, and I can’t quite understand it because the clay wasn’t that good— it was strictly a mediocre clay. I do know this: the Bay State property went across the Alewife Brook Parkway, and that entire development across the street, where you now have industrial development at Rindge Avenue Extension and that area, is all built on clay. If you don’t believe me, there’s a building over there, built directly after the war, and they insisted on waiting for a supply of the genuine original Harvard water-struck brick. They put it up and then found that improper footings were put in. They knew it was clay land, they knew there were bogs, and almost immediately had the heartbreak of a very badly cracked building.

All of these people—these individual yards, all from the same area basically—were trying to fight for the same jobs. Obviously in that whole area no one man could get it all, and so it was dog-eat-dog almost from the very start, and the Bay State Brick Company didn’t last long. One interesting thing surprised me: in 1890 a big series of posters and handbills for help wanted were printed— in English and in French. During my experience with brickyarding, the Frenchmen were all in New Hampshire and Maine, but the Italians were in this area. Maybe you have a bigger French population than I realize.

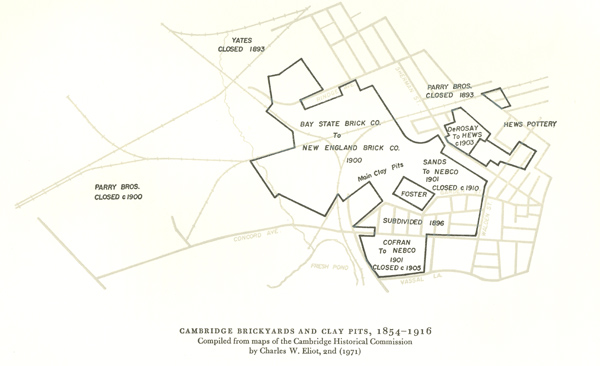

On October 31, 1900, the Bay State Brick Company transferred all its holdings to the New England Brick Company. This new company evidently had the avowed purpose of getting rid of the confusion of many small manufacturers. Some of the new names that appeared may be familiar to you; they are all familiar to me through my association with the industry. A. E. Locke was the president, Harry Bemis was the vice-president, Thomas Lacey was clerk, and there was a director named G. Irving Tuttle. We had a bookkeeper—as fine a gentleman as I have ever met—whose name was Rowland Russell; I find that back in 1900 and for several years thereafter he was the auditor for the New England Brick Company. This company had a lot of familiar names, particularly well known to anyone acquainted with the contracting business. It comprised thirty-six brickyards, all open yards with this original process of brickmaking that I described. It operated in Maine, New Hampshire, and New York as well, with the headquarters in Massachusetts and yards in all this Cambridge area, in Somerville, Belmont, Arlington, Chelsea, and Medford. Here again Professor Eliot gave me some information taken from the book Cambridge Fifty Years a City, 1846-1896: the number one on the “Hit Parade” for brick were the Parry Brothers, who have twice as much on their operation as the Bay State Brick Company. There is also quite a bit on a gentleman I never heard of, D. Warren Rosay. The claims here are far from modest as to what they did. I think they knew a politician. However, be that as it may, the Parrys did have a yard here and also in New Hampshire and they were great friends of my family’s. I knew many of them and I think there is only one left now and I am not sure if John is still alive (the cousin John).

I won’t say that the grand motif of the New England Brick Company as it was presented in 1900, with its somewhat idealistic dreams, was completely fulfilled, because when you have such people as were in there, everyone feels he is not getting his just share. Since I mentioned the Parrys, I know that was true of them; they were squabbling all the time, and they finally left the combine and had their own place off Concord Avenue, which later became a yard for face brick and so forth which they bought and sold. The New England Brick Company in its old form lasted until 1923. In that year it went through the last reorganization. It was then owned exclusively by three men, and through a series of interesting events it now wound up into one family. It no longer manufactures, it is still in the brick business, but it is also in many allied fields; pretty soon I think the tail is going to wag the dog because we are in the field of pollution and anti-pollution devices, and the way the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and every other state in the Union is going, it looks to me as though we will have a misnomer in four or five years if things go as they have gone.

Extracts From Discussion

From audience: In Williamsburg, I heard that the difference in color in the brick was due to the difference in the wood used in drying the brick.

Mr. Long: I know what you are talking about. We are going back now to the day of hand-made brick and the stove-kiln. We are also going back to the day where the number one fuel for making brick was wood, and wood contains potash, and potash does wonders for developing the color in brick. Now you are talking about the glazed headers that look like glass. This is because the heat was brought up to the point where the end of that clay turned into a glass-like substance, a glaze. Today they charge an ungodly amount to get that effect, an effect which was just as natural as your grandmother baking a pie. It is all done by wood burning and that is what our Harvard water-struck brick are, where they get those beautiful colors. And they get the same effect and you can burn green, grays, black, yellows —this is natural from the clay. You have no control over what you are getting.

From audience: We have a house in Maine and were so glad to get old brick for our chimney and fireplace, but have been sorry since because every spring when we go down there the red is splotched and streaked with white. The dampness seems to come through and it takes us half the summer to get it dried out.

Mr. Long: I hate to talk against the ladies, but you are forcing my hand. That old brick you are talking about—the ladies will say how beautiful it is, how wonderful it is, and then they will give you the argument that it has been tested through the ages, that it has stood up so this will be a wonderful thing to have. Actually, God bless them, they are all wrong. It has stood up through the ages, but it has stood up on the inside of a wall where it never got any water, and when you put it on the outside, it wasn’t made for it, and it’s going to absorb water and it’s loaded with salts from previous use. It’s going to leak, it’s going to do all these things you say, I’ll guarantee it.

From audience: Harvard had to give up its Georgian architecture on account of not being able to get hand-made brick. They tried to do one building at the Business School without it and it just doesn’t look right.

Mr. Long: I’m not going to dispute a word you say, but I will state that we put ten million hand-made brick into the Harvard Business School.

From audience: It doesn’t look right.

Mr. Long: Don’t blame the brick if it doesn’t look right. An architect says, “This is what I want,” and ten years later someone says, “Isn’t that horrible?” They can get hand-made brick today if they want it. Now on this particular job that you are talking about, on many of those jobs over there, and I was connected with some of them, they inspected every truckload of brick that came in by climbing up on the scaffolding and looking down at the truck, to make sure that what they saw on the truck was the same as what they saw on the building, and that was done before any truck was permitted to be unloaded. It’s the only place I ever saw that happen.

Mr. Eliot: We have certainly learned a lot about the making of brick, and a lot about the Cambridge brickyards. I was particularly interested in the reference to the handbill trying to get new employees, being printed in French. As some of you may be well aware, there is a very considerable colony of French-Canadians in the area just north of that shown on the maps and I assume that group was what they were aiming at. You didn’t mention another group of people that I assume were in that neighborhood, because when I looked at these old maps I found that in the middle of the last century, Sherman Street was known as Dublin Street.

Read March 28, 1971

Unfortunately, Mr. Long did not have an opportunity before his death to review the transcript of his talk.—Ed.

This article can be found in the Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society Volume 42, from the years 1970-1972.