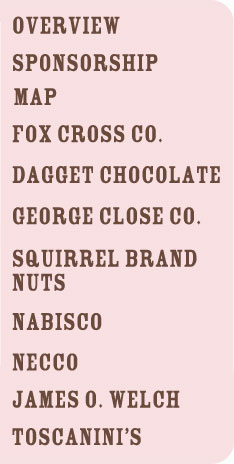

The tour begins in Kendall Square, and with the high-tech firms and pharmaceutical companies that now dominate the landscape, I know it’s hard to image that fifty years ago in Cambridge, candy was king. Main Street was once affectionately called Confectioner’s Row, and the companies here made products that are still known and loved today: Junior Mints, Charleston Chews, Sugar Daddies, and NECCO wafers.

The area’s confectionery past begins way back in 1765 when an Irish immigrant named John Hannon established America’s first chocolate mill on the banks of the Neponset River in Dorchester. Soon after, candy companies started as roadside operations: the proximity of the chocolate mill, plus nearby sugar refineries and a large city population made the area ideal for the new industry. Soon, companies Royal, Cole, Haviland and Liberty made chocolate in Boston, and to the east in Charlestown was the boxed-chocolate giant Schrafft’s.

Then, with the introduction of the steam engine, local companies began producing the first candy-making machines. In 1847, Oliver R. Chase made a lozenge cutting machine and began to produce the wafers later known as NECCOs. Successful confectioners soon outgrew their Boston factories and decided to expand production in Cambridge, where more land could be bought for less money.

For the next 100 years, Cambridge was a major industrial center and candy making was one of its largest industries. In 1910 there were 16 confectionery manufacturers listed in the city, by 1920 the number was 30, and by 1930 there were more than 40. At its peak in 1946 there were 66 candy manufacturing companies listed in the city’s directory.

The beginning of the end for Cambridge candy came with the rise of the big national candy conglomerates, namely Hershey’s, Nestle and Mars. These companies understood that distribution had changed. You had to get involved with the big chains, and you had to be more centrally located, where you could ship everywhere. Success in the industry became less about who was producing the best candy and more about who could get to market first. Independent confectioners were hard pressed to match the conglomerates’ distribution levels, national marketing efforts, and slotting fees, which is the price companies pay to have their candies front and center of the register at the grocery store.

This tour will touch upon what’s left of Cambridge’s candy legacy, and will also mention other sweets, like cookies and ice cream, which also have histories here.