The Reverend Jose Glover And The Beginnings Of The Cambridge Press (Part 1)

by John A. Harrer, 1960

This article can be found in the Proceedings of the Cambridge Historical Society Volume 38, from the years 1959-1960.

The most famous antiquarian sale of books America has known was held in the year 1879. None other has equaled it in the eighty years that have passed since then. The great collection of books, on display for the occasion of the sale in the auction rooms of Messrs. George A. Leavitt & Co., New York, and gathered through the lifetime of a collector’s experience, had been the property of Mr. George Brinley of Hartford, Connecticut. A printed catalogue listing and describing each book could be purchased in advance. A few of these had been printed on special high grade paper. The catalogue itself, expanded with subsequent sales, continues to be of importance to collectors. On page 95 of Part I those who attended found two copies of one book described. The first sold for $150.00 and is now safely lodged in the William L. Clements Library, Ann Arbor, Michigan. The second was purchased for the Congregational Library at a price of $50.00 and, since the book, A Platform of Church Discipline, is the basic authority for Congregational church government, it is more appropriately at home in its location than any other of the nine copies in existence.

This book is not just one of the rare books of early days. It is a fundamental colonial document. At the time of its three-hundredth anniversary Dr. Henry Wilder Foote wrote concerning its origin, contents, and meaning as they relate both to religion and to American history. His final point shows the Platform to be “the seed-bed from which those doctrines had sprouted” leading to the Revolution. And for free church government it is the carefully prepared statement produced by learned and determined men who had tested their beliefs with Biblical teachings and were convinced that God had guided them. During three hundred years there have been thirty-five editions.

We can thus understand that of all the books that came from the Cambridge press this one is among the few to be regarded as most precious. That it is the cornerstone of American Congregationalism has led me to a study of the Cambridge press and its origin. As a result I soon found myself in the middle of Massachusetts colonial affairs during the era in which the first settlers were establishing themselves, building churches, schools, and government. Most characters in the story soon became real people. There were those who originated ideas to foster the press. Others wrote the books, sermons, and pamphlets printed by it.

A Ph.D. dissertation on the history of the Cambridge press by Dr. Lawrence G. Starkey is comprehensive and detailed. It is the most recent of a number of studies dealing with this theme. Anyone who wishes to see the true picture will also read the earlier writers, some of whom are listed in our short bibliography. The single most important book is that of George Parker Winship, former Harvard librarian, whose narrative of the press can be read rapidly. Students will do well to place the volume within easy reach to reread its detailed sections.

One section of Winship’s book relating to the Platform of Church Discipline caught my attention. I thought I might have found a mistake in the story of its printing. After examining the original, and after writing to libraries and individuals who have copies of the Platform, my suspicions were confirmed. A little later, however, I came upon Dr. Starkey’s article in Studies in Bibliography, “The Printing by the Cambridge Press of A Platform of Church Discipline, 1649.” My interest in having discovered Winship’s error was dampened. Starkey’s study had already demonstrated the same facts. I was about to give up when I came upon a note of correction in a later copy of the same periodical stating that Dr. Starkey had also arrived at a wrong conclusion in regard to one phase of the printing. So I resumed my efforts, expanding the original plan to include additional categories. The bibliographical details do not need to be repeated; the reader may consult the article. However, one section of this present paper supplements what is there explained. A number of the points are here described in nontechnical language. To the title of this paper we might well have prefixed the words, “Footnote to the story of.” A slightly different slant is given to Matthew Day’s last work and the taking over of the press by Samuel Green. The indication of the present location of the nine copies of the Cambridge Platform, and the fact that each owner can find his Platform within one of four variant states, will also have an interest for some.

The reason for “Reverend Jose Glover” in the title of this paper is to draw attention to a more or less forgotten name, and to recognize him as the founder. There is no card for his name in the catalogue of many libraries where one might expect to find it. In 1810 Isaiah Thomas said of him, “Although he was one of the best, and firmest friends to Newengland, his name has not been handed down to us with so much publicity as were those of other distinguished characters, who were his contemporaries.” This continues to be true. None but antiquarians would recognize his name today. Having read a number of accounts which give the biographical facts concerning Jose Glover, I have told the story in as free a style as I could manage. Others have quoted from Governor Winthrop and Hugh Peter and from several other available contemporary writings, all of which are brief. Most of the facts about the Glover family I obtained from Winship and from Isaiah Thomas. A search in Sutton, Surrey, and in the libraries of England would no doubt yield additional material and provide data for a biography.

Printing in the United States dates back to early colonial days. Boston was settled in 1630. The year 1638 brought the printing press to Cambridge fifty years in advance of its appearance in any other colonial settlement. New York’s first press began operation in 1693, Philadelphia’s in 1685. The General Court of the Bay Colony permitted the establishment of no other press within its jurisdiction for nearly forty years. Marmaduke Johnson moved his press from Cambridge to Boston in 1674. Having, therefore, a monopoly during more than half of its life span, the Cambridge press was in business from 1638 to 1692. Every item printed then has become a rarity, a valued possession of any individual collector or library. Such early examples of the printing craft are sometimes called American incunabula, that is, the babyhood of American printing. Of three thousand who sailed for New England in the summer of 1638 one man, a Puritan clergyman, was interested in printing and had done something about it. New York, despite its early founding, long remained without a press. This could have been true for Massachusetts. The initial printing enterprise might have been delayed for decades. This is the reason Mr. Glover deserves the highest credit. Since he is the prime figure of all personalities we shall meet in our narrative, it is desirable to become acquainted with him and his family.

II

In the year 1624 Rev. Jose Glover came to his first church in the village of Sutton in Surrey, about fifteen miles south of London. Shortly before this he had married Miss Sarah Owfield, who brought with her a generous dowry. The young clergyman, himself from a very prosperous family, was the son who had chosen the church for his portion in life. His father was generous, providing him with ample resources. The free parsonage, the stipend, and their own fortunes allowed the couple to furnish their house with every comfort. If they could not have a washing machine they did have servants who achieved equally good results. No doubt a coach and horses carried the young parson on his pastoral rounds and him and his wife to social engagements. One of the main commercial enterprises of his father and brothers was shipping. Their argosies returned with profits as a result of successful trading in the West Indies. Later, when the largest number of Puritans crossed the Atlantic to New England, the Glover ships transported many people and their goods.

Despite the favorable beginnings of the marriage, which in due time brought three children to the couple, the story is punctuated with tragedy. Young Mrs. Glover died after only four years of life in the Sutton parsonage. Before long Glover became acquainted with and married Miss Elizabeth Harris, the daughter of a near-by clergyman. She brought with her no money, but she filled her new position within the busy household in a most creditable manner. Another son and another daughter resulted from this marriage. Father and mother, two boys, and three girls, with several servants, now made up the menage. The family might have lived happily ever after in their pleasant abode if Mr. Glover had not been a Puritan. Acquainted with the Winthrops, a connection of Roger Williams, his thoughts turned more and more toward New England. Transportation was no problem. When the time came he embarked in a Glover sailing vessel. His Puritanism was, possibly, not of the most vigorous type. Sabbath observance, however, had become an issue. The Puritans were determined. The purity of the church was at stake. A little slower than some of his brother ministers to raise points of disagreement with the established church, the Sutton clergyman now took his stand. He refused to obey instructions to read the Book of Sports in the church service.

Some years before, the King had signed a Declaration to allow pleasurable recreation on Sunday afternoon. This regulation which was called the Book of Sports, was required to be read from the pulpit. It might have been set aside and forgotten because of Puritan opposition. But Bishop Laud had come into power. Here were means at hand for him to carry out his purposes to separate sheep from goats, the nonconformist Puritans from those who were obedient to the Church of England. He engaged in vigorous and successful persecution, searching out, in their hiding places, all enemies of the church. He found many. Rev. Jose Glover was forced to give up his charge in the year 1636. His social position and the prominence of his family, no doubt, protected him. He was not harried out of the land. Preparations for departure were made without haste. No difficulty arose when the time came to leave England.

The years from 1630 to 1640 were the period of the Great Migration, beginning and ending quite abruptly. Nearly twenty thousand settlers came from old to New England, entering Boston harbor to settle in Salem, Rowley, Cambridge, Boston, Dorchester, and Dedham. Of all these thousands only one man, Rev. Jose Glover, had an idea different from any one else, namely to bring a printing press. He sailed in 1638. The little ship was made ready in the Thames at London in mid-summer. Mr. Glover, his wife, and five children were on board. So were furniture, linen, silver, clothing, horses, coach, wagon, men servants, maid servants, and some cattle. Stowed away in the hold were the printing press, type, many reams of paper, type cases, ink, and printers’ tools. Not one necessary item was omitted. As the waters of the high tide began to flow, the boat moved along the estuary into the deep ocean.

Two or three years had passed since Glover had decided to cross the Atlantic to New England. His active mind had mapped out a future that demonstrated his resourcefulness and his realization of two areas of growth in the new world to which he expected to give most of his attention, the college and the printing enterprise. He might become president of the one and owner of the other. The ministry was his calling. Unfolding events would determine whether teaching or preaching or both would receive chief emphasis. He had already invested quite substantially in New England real estate, which would also require a portion of his time. Finally, church people in England for some years had felt a compulsion to save the souls of American Indians. Every one of these fields of endeavor was upon his mind as he speculated on the variety of possibilities for the employment of his printing press. He probably did not anticipate that a Psalm Book would be its first production. He did not know that the language of the Indians would make demands on his press beyond anything else. Sermons, college theses, commencement programs, text books, laws of the colony, new polity for churches — these he was ready to print, and he may have anticipated all of these needs.

In midocean Glover contracted a fatal illness. It was probably smallpox. Since Puritan clergymen saw all happenings in the language of the Bible, it is not unlikely that, thinking of Moses, he besought the Lord that he might be spared to go into the Promised Land, and feared also the answer, “Thou shalt not pass over this Jordan.” He was buried at sea. With forethought he had prepared for others to care for his printing press and to give the new enterprise its start. They did not fail him.

The small boat with his wife and children sailed on and at last glided slowly into Massachusetts Bay. Watchers from the shore had sighted an unusual number of sails that year. As the “John of London” gently advanced through the waters of the bay, five Glover children gazed toward the shore. Which one would be first to see an Indian? As they stood in a row lined up by age, fifteen, thirteen, eleven, seven, and five, it was to be noted that the youngest and oldest were boys. Two of the three girls later married Adam and Dean Winthrop, sons of the Governor.

The little vessel sailed on past the Boston wharf to Charlestown where the horses were taken from their cramped quarters, harnessed, and hitched to the coach which carried the family along five miles of flat roadway to Cambridge. The mansion house of Governor Haynes had already been purchased. Fireplaces were soon ablaze and the chill of fall air was driven out. The children ran through the empty rooms, looked out of the windows, still hoping for the first Indian. They saw other buildings on their land as they stood looking from the back windows. Some have thought the printing press was first established in one of these structures. There seems little doubt, however, that the Day home was the first location.

III

Before leaving England Mr. Glover and Steven Day, with the latter’s son, had entered into an agreement which has been studied and described so many times that we here state only that the father, a versatile craftsman, worked at and supervised the assembling and setting up of the printing press in its new home. Steven Day also continued as proprietor of the enterprise for a few years. Since Matthew Day, the son, had more business ability than his father, he no doubt was soon guiding affairs on the spot. Mrs. Glover purchased a house for the Day family in Crooked Street, now Holyoke Street. It is probable that the press was placed in one of the rooms of this house, where it remained for five years (1638-1643). The Bay Psalm Book, the first book to be printed, had its origin at this first location, and for it part of Mr. Glover’s supply of paper was used. The press was then moved to the newly erected president’s house in the Harvard yard just inside the gate opposite the Unitarian Church, where it remained from 1643 to 1655. Here the laws of the colony were printed in 1648, and the Cambridge Platform in 1649. The final location of the press was the first floor of the Indian College on a rise of ground, now somewhat leveled off, approximately where Houghton Library now stands.

The ship which brought Henry Dunster, first president of Harvard, arrived in 1640. An eligible bachelor, he soon met and married Mrs. Glover. They lived in the Glover home only two years before she died, leaving in his care five children, the affairs of the estate, and the proprietorship of the printing press. Mr. Dunster soon married again, which necessitated the winding up of the estate to protect the inheritance of the children. A house was then built for Harvard’s president in the college yard, and, as indicated, the printing press was placed in one of its rooms. The press now became an appurtenance of the college, its ownership somewhat confused, although Matthew Day managed it under Mr. Dunster’s direction. This arrangement continued until Matthew Day died at the age of thirty, in the year 1649. While our present interests do not reach beyond this date, it is well to state that events of the year 1655 brought a new president to Harvard and the removal of the press to the Indian College, where it continued to operate until 1692, a span of thirty-seven years.

IV

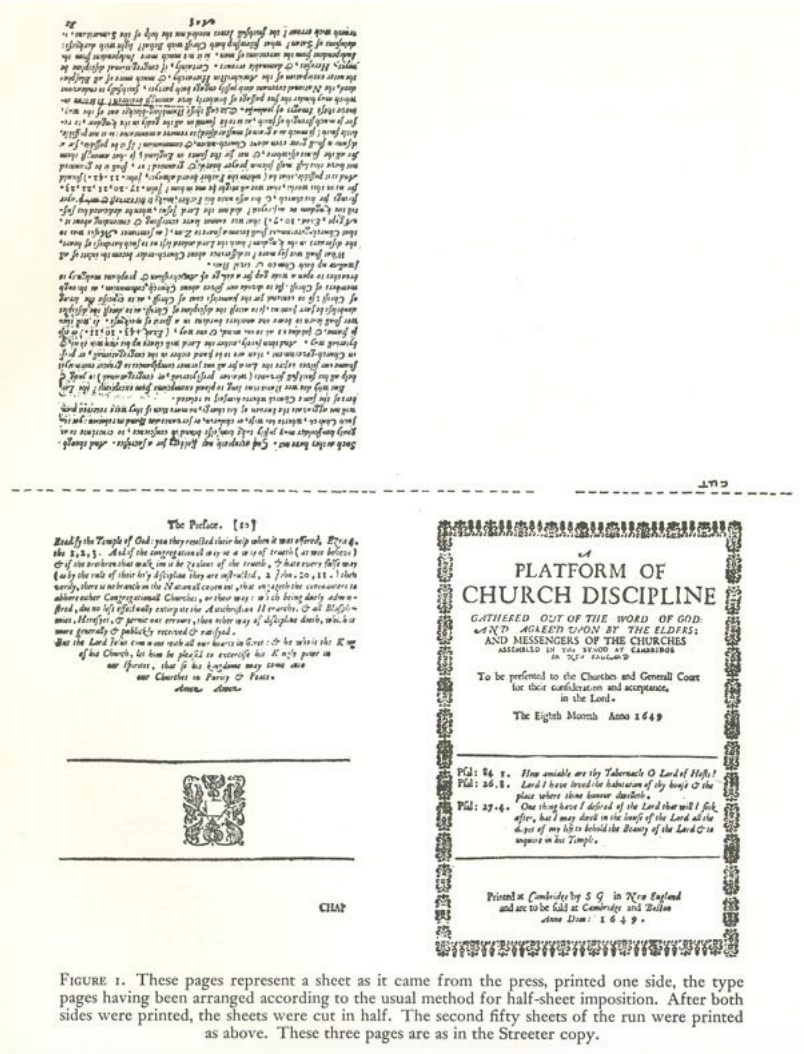

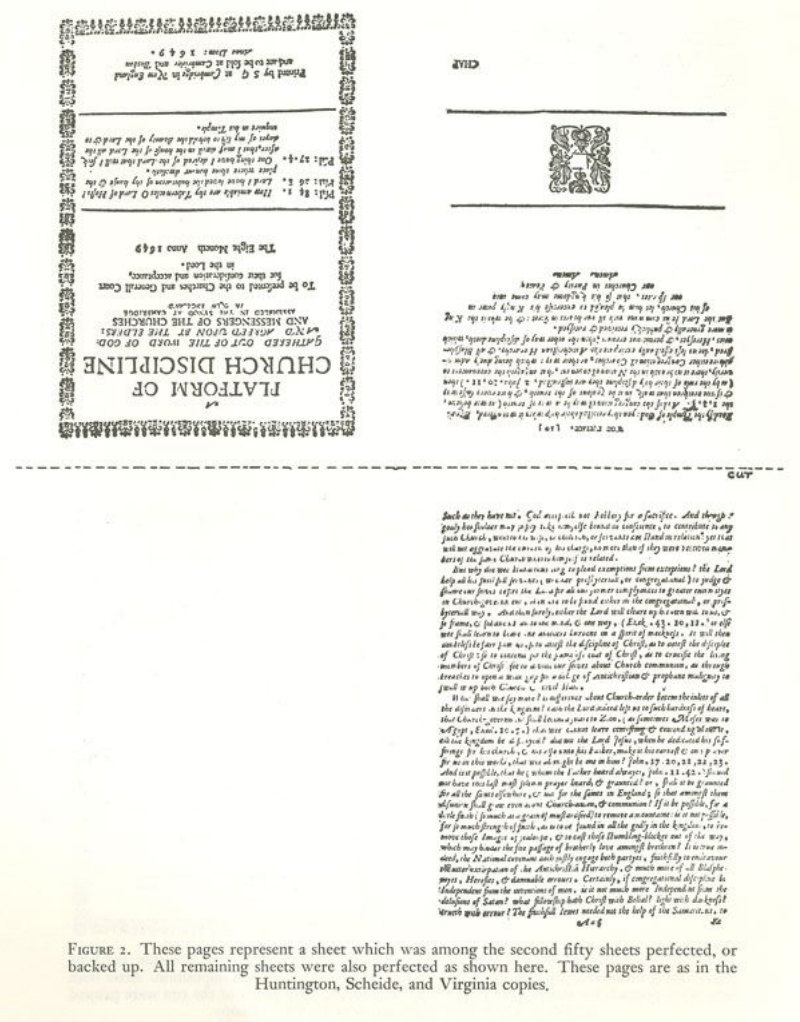

Since our subject is that of a publishing establishment, we shall examine the actual printing of one of the most remarkable books of the press, the Cambridge Platform. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries any copy of the Cambridge Platform, 1649, has been an object to be coveted. Only a few collectors were fortunate enough to secure one. Early, possibly in the middle of the nineteenth century, two variant states were recognized within the edition of approximately 500, the difference due to changes in the title page after perhaps one hundred copies had been printed. No satisfactory study of the composition and presswork was attempted until George Parker Winship’s remarkable book in 1945 provided a comprehensive history of the Cambridge press. In it he drew attention to an error on page 9 of the Preface, the significance of which rested on the fact that this page was printed on the same sheet with the title page. As already noted, Dr. Lawrence G. Starkey’s article corrected errors in Winship’s presentation, though he himself was mistaken in regard to one operation of the printing, his theory concerning cut-sheet printing being changed in a later note of correction.1 The article, with its correction note, is the only scholarly, bibliographical study of the printing of the Cambridge Platform and should be read by all students interested in this theme.

The General Court of Massachusetts had invited the churches of New England to meet in September, 1646, to discuss and clear up questions of church government and discipline which they judged agreeable to the Holy Scriptures. At this Synod Richard Mather, John Cotton, and Ralph Partridge were appointed, each to write his own report for presentation at the Synod on June 8 a year later. Because of an epidemic of illness this second Synod adjourned after ten days of discussion to meet in the late summer of 1648. When at last messengers and clergy met, only two weeks were needed to study and compare the three documents. That of Richard Mather was chosen. John Cotton provided a preface, which was probably one section lifted from his manuscript. The manuscript of the platform prepared by Ralph Partridge of Duxbury has been preserved along with that of Richard Mather. Both are in the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts. The plan presented by John Cotton has been lost.

Printing of the small book was completed about a year later. Approved by the Synod in the late summer of 1648, it came from the press in the late summer of 1649. Winship states, “Widespread public interest would have urged speedy publication.” What then could have delayed itsprinting an entire year? There are several answers. An accurate, readable copy had to be made for the printer. The editorial tasks may not have been taken care of promptly. Finally, the printer, Matthew Day, became ill and died May 10, 1649. His illness was, quite likely, the culminating reason why publication was held up. Whatever the causes of delay its printing needed to be completed before the meeting of the General Court in the fall of 1649. The statement on the title page can be accepted at its face value. The printing was finished “The Eight Moneth Anno 1649.” This date has also been considered a mistake that should have read 1648, the date when the document was completed and approved by the Synod.

Only one product of the press, the almanac for 1647, has the name Matthew Day in an imprint. Either he was very modest and slow to assert his rights or Mr. Dunster may have interfered. As printer in charge of the press for twelve years, Day certainly looked forward to the printing of the important Platform of Church Discipline. He had just completed The Book of the General Laws, 1648. Since there were months of time following the completion of this official assignment of the General Court, it is very likely that he promptly began the work of preparation of the Platform, which was also the concern of the lawmaking body. There can be little doubt, it seems to me, that he designed and composed the title page and started his plans for the book itself. Williston Walker2 plainly sets forth the time of printing, showing that the book had been completed and was presented to the General Court in October.

Curiously, those who have described the book differ in their opinions, some considering it poorly printed, or the title page too crowded. Others declare it remarkably well done, too nicely arranged for a novice such as Samuel Green. To me the title page, at least, is something of a work of art. That there is reason to declare Matthew Day to be its compositor rests on three facts. The first is that he could hardly have failed to turn over in his mind exactly what he would do to attain the best possible result. He knew that it would be examined immediately by clergy and lawmakers. The title page offered the best chance to display his skill. The second fact is the practice of preparing the title page first. By some who have examined the printing of this book it is taken for granted that the title page of this particular book was prepared and printed last.

Winship3 states it was “the last to go to press.” This differs from the following by Charles Evans4: “the practice customary with the early printers, of printing the title page first.”

In the case of books with no preface or preliminary introductory material, the title page would normally be printed first as part of the initial gathering. In this book, however, there is a preface, and its signatures are differentiated from the main body of the Platform. It is always assumed that in such a case the title page was printed last. Even though the title page was printed last, however, I think it had been composed by Matthew Day and left standing. Accustomed to prepare the title page first for some books, Day would have found this one of such importance as to excite his interest and encourage him to design the title page early.

The third point is this. George Parker Winship interpreted the action of the General Court taken in the fall of 1649 to mean that the book was printed subsequent to that meeting. Since there is very little doubt that this is a mistaken conclusion and that the printed Platform was in the hands of its members at this time and was then simply recommended to the churches, the date of printing is moved back a considerable space of time and the start of its composition almost certainly reaches back several months. It is my theory that the book was planned and partly composed by Matthew Day. Errors which remained uncorrected were due to his illness which put an end to all work. Nevertheless, preparatory efforts were soon turned over to Samuel Green. However, much of the work had been done before he took over, the book was now his. He was now proprietor of the press, a position he held for forty-three years.

Antiquarians, of course, make mention of the Platform as Samuel Green’s first book. But it is well established that he took over because of an emergency and so found himself in the middle of whatever items of work were in process, whether nearly completed, half finished, or just started. The likelihood is that the Platform had been given a good start and may have been half way along.

We are not here attempting to ascribe the Platform to Matthew Day as his last book. The meticulous, almost errorless work on the Laws was his final monument. But we are setting forth a fairly obvious theory that he designed the Cambridge Platform and composed some of it. Littlefield states, “He literally died in harness.” Eight pounds were due him for printing, part of which was probably for the hours spent at the work we have just described. It is thus a reasonable theory that Samuel Green was the fortunate inheritor of a well-composed title page plus additional pages to launch him in his first effort, the printing of the Cambridge Platform.